| Absinthe History and FAQ I |

| Welcome to the most detailed, accurate and comprehensive Absinthe FAQ on the web. |

| Version Française |

FAQ I

What is absinthe?

How is absinthe drunk?

FAQ II

What gives absinthe its “secondary effects”?

What is wormwood? What is thujone?

Which modern drinks are related to absinthe?

What does absinthe taste like? Is it very bitter?

Where does the word "absinthe" come from?

What is absinthe?

How is absinthe drunk?

FAQ II

What gives absinthe its “secondary effects”?

What is wormwood? What is thujone?

Which modern drinks are related to absinthe?

What does absinthe taste like? Is it very bitter?

Where does the word "absinthe" come from?

FAQ III

What is the history of absinthe?

Who invented it?

Which were the best quality absinthes?

What did they cost?

FAQ IV

How did absinthe influence artists like

Degas, Manet, van Gogh and Picasso,

and writers like Verlaine, Rimbaud,

Wilde and Hemingway?

What is the history of absinthe?

Who invented it?

Which were the best quality absinthes?

What did they cost?

FAQ IV

How did absinthe influence artists like

Degas, Manet, van Gogh and Picasso,

and writers like Verlaine, Rimbaud,

Wilde and Hemingway?

FAQ V

Why was absinthe banned?

What was absinthism? Who was

Dr Valentin Magnan?

FAQ VI

What were the Lanfray murders?

When was absinthe banned?

What happened after the ban?

The modern absinthe revival

Why was absinthe banned?

What was absinthism? Who was

Dr Valentin Magnan?

FAQ VI

What were the Lanfray murders?

When was absinthe banned?

What happened after the ban?

The modern absinthe revival

What is absinthe?

Absinthe is a strongly alcoholic aperitif made from alcohol and distilled herbs or herbal extracts, chief amongst them grand wormwood

(Artemisia absinthium) and green anise, but also almost always including 3 other herbs: petite wormwood (Artemisia pontica, aka

Roman wormwood), fennel, and hyssop. Some regionally authentic recipes also call for additional herbs like star anise (badiane), sweet

flag (aka calamus), melissa (aka lemonbalm or citronnelle), angelica (both root and seed), dittany (a type of oregano grown in Crete),

coriander, veronica (aka speedwell), marjoram or peppermint.

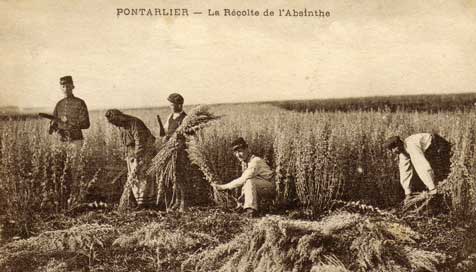

Grand and petite wormwood were historically cultivated near Pontarlier in the Doubs region of east France and in the adjoining Val de

Travers in Switzerland, the two traditional homes of absinthe, while the other herbs were shipped in: fennel from the Gard region of France

and even from Italy, the anise from the Tarn region or from Andalusia.

In modern Spanish absinthes star anise (badiane) is sometimes substituted wholly or partly for the green anise, but this tends to give a

very one dimensional liquorice-like taste. Badiane was used only very sparingly if at all in traditional Swiss or French manufacture. So

called Czech or German "absinths" sometimes omit the anise entirely, but these are not true absinthes and are best avoided. Home

"absinthe-making kits" widely advertised on the internet, and based on adding dried herbs or essences to vodka or Everclear, do not

produce even a rough approximation of the real drink - and the results, apart from being very unpleasant tasting, may be actively harmful.

High quality absinthes are always distilled rather than produced from herbal essences, and have a deliciously complex herbal and floral

character, with an underlying bitterness caused by the wormwood. The classic green absinthe verte is produced by a 3-step process: first

maceration of the herbal mixture in a base alcohol, then distillation of the resultant liquid and finally chlorophyllic coloration by gentle

heating of a further herbal infusion.

The absinthe distillation process was summarised by J. de Brevans in his 1908 La Fabrication des Liqueurs as follows:

Absinthe is made in accordance with a great number of recipes which are all based upon the following plants: grand wormwood, petite

wormwood, anise, fennel, and hyssop. In general these different plants are mixed together for distillation; but a few manufacturers prefer to

treat wormwood, anise and fennel separately, to later mix the scented spirits in the desired proportions.

The raw ingredients are placed into a steam-heated still, ...with the desired quantity of alcohol and half the volume of water needed for

distillation; the plants are allowed to macerate 12 to 24 hours or even longer; the rest of the water is added and distillation is started. ...This

operation is stopped as soon as the first spurt of distillate marks 60% (alcohol): rectification is thereby avoided.

The first part of the tails is collected separately and used to make absinthes ordinaire; only the heart is used to prepare fine absinthes. The

milky liquid which distills at the end is added to subsequent macerations.

Absinthe scented-spirit is colorless. To color it, a mixture of petite wormwood and hyssop is macerated; a colorator, a special apparatus

heated by steam or hot water circulation, is useful for this purpose; the process takes 12 hours.

Absinthe is put into barrels for aging, then reduced to desired proof before delivering for consumption.

Each herb adds its own subtle character to the blend - grand wormwood has both woody and bitter notes; petite wormwood is aromatic but

less bitter (and also useful for coloration); green anise gives its characteristic scent and rich smooth mouth-feel (which fennel also

enhances); the dried hyssop flowers contributes to the classic absinthe feuille morte (dead leaf) colour.

Well made absinthes are generally pale green, but louche, or turn milky, when water is added. This is caused by the essential oils

precipitating out of the solution, as the alcohol is diluted. Absinthes with a high percentage of star anise (or badiane as it is known in

France), such as those made in Spain, tend to have a very dramatic and opaque louche, while the louche in more traditionally made

absinthes develops slowly, and is more subtly translucent. Traditionally made absinthes are never a bright emerald green - those that are,

have artificial colouring added.

Clear absinthes - often called La Bleue or La Blanche, and historically popular in Switzerland - are made without the final colouring step,

and may also differ slightly in herbal composition (sometimes for instance containing génépi, which is not otherwise usually found in

absinthe). A red absinthe (originally probably coloured with paprika) has been made under the name Serpis for several decades in Spain,

but this is an isolated oddity.

The traditional strength is 55% - 72% alcohol, or 110º - 144º proof. Historically the best absinthes, including those from Pernod Fils, were

made from a base of grape alcohol, although cheaper grain or beet alcohols were also widely used.

Almost from its inception, absinthe has been known as “La Fée Verte” or “The Green Fairy”, a tribute to its reputedly seductive and

intoxicating powers.

How is absinthe drunk?

All true absinthes are bitter to some degree (due to the presence of absinthin, extracted from the wormwood) and are therefore usually

served with the addition of sugar. This not only counters the bitterness, but in well made absinthes seems also to subtly improve the

herbal flavour-profile of the drink.

The classic French absinthe ritual involves placing a sugar cube on a flat perforated spoon, which rests on the rim of the glass containing

a measure or “dose” of absinthe. Iced water is then very slowly dripped on to the sugar cube, which gradually dissolves and drips, along

with the water, into the absinthe, causing the green liquor to louche (“loosh”) into an opaque opalescent white as the essential oils

precipitate out of the alcoholic solution. Usually three to four parts water are added to one part of 68% absinthe. Historically, true

absintheurs used to take great care in adding the water, letting it fall drop by single drop onto the sugar cube, and then watching each

individual drip cut a milky swathe through the peridot-green absinthe below. Seeing the drink gradually change colour was part of its

ritualistic attraction.

One of the most evocative of all descriptions of the absinthe ritual is in Marcel Pagnol's The Time of Secrets:

"The poet's eyes suddenly gleamed.

Then, in deep silence, began a kind of ceremony.

He set the glass - a very big one - before him, after inspecting its cleanliness. Then he took the bottle, uncorked it, sniffed it, and poured out

an amber coloured liquid with green glints to it. He seemed to measure the dose with suspicious attention for, after a careful check and

some reflection, he added a few drops.

He next took up from the tray a kind of small silver shovel, long and narrow, in which patterned perforations had been cut.

He placed this contrivance on the rim of the glass like a bridge, and loaded it with two lumps of sugar.

Then he turned towards his wife: she was already holding the handle of a 'guggler', that is to say a porous earthenware pitcher in the shape

of a cock, and he said:

'Your turn, my Infanta!'

Placing one hand on her hip with a graceful curve of her arm, the Infanta lifted the pitcher rather high, then, with infallible skill, she let a very

thin jet of cool water - that came out of the fowls beak - fall on to the lumps of sugar which slowly began to disintegrate.

The poet, his chin almost touching the table between his two hands placed flat on it, was watching this operation very closely. The pouring

Infanta was as motionless as a fountain, and Isabelle did not breathe.

In the liquid, whose level was slowly rising, I could see a milky mist forming in swirls which eventually joined up, while a pungent smell of

aniseed deliciously refreshed my nostrils.

Twice over, by raising his hand, the master of ceremonies interrupted the fall of the liquid, which he doubtless considered too brutal or too

abundant: after examining the beverage with an uneasy manner that gave way to reassurance he signalled, by a mere look, for the

operation to be resumed.

Suddenly he quivered and, with an imperative gesture, definitely stopped the flow of water, as if a single drop more might have instantly

degraded the sacred potion."

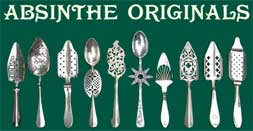

Antique perforated spoons for use with absinthe are prized collectors items. There are hundreds of variants, some issued to

commemorate historic events like the opening of the Eiffel Tower in 1889, some representing intertwined absinthe leaves, others with

engraved advertising for one of the famous brands of the day. Almost all have been exhaustively catalogued by Marie Claude Delahaye, the

leading French authority on absinthe and absinthiana, and the author of numerous books on the subject.

A more unusual and labour-saving alternative to the perforated spoon was the absinthe brouilleur, a mixer that sat on top of the glass and

held both water and sugar, allowing the sugared water to automatically drip slowly into the glass. Also avidly collected are glasses,

carafes, ceramic pitchers and water fountains made specifically for use with the absinthe ritual.

There is some debate amongst absinthe historians as to when exactly the traditional absinthe ritual originated. Certainly, there is no

evidence that it was ever normal to drink absinthe neat, without water. Absinthe was drunk with the addition of both water and sugar from at

least the 1850's, and probably earlier. Absinthe was by no means unique in this respect - 19th century drinkers had a far sweeter tooth

when it came to alcohol than we have today, and other drinks and cordials were also regularly sweetened with sugar. They were usually

served with a long cordial spoon or a kind of swizzle stick, to help dissolve the sugar.

The use of a perforated spoon specifically for absinthe was a later development, which appears to have originated in the 1870's and only

became widespread in the 1880's and 1890's. From the 1890's onwards, it seems, on the evidence of existing engravings and cartoons,

that almost all absinthes in bars and cafés were served with a perforated spoon. However most satirical journals and such like reflected

specifically the Parisian scene, and it's possible that in far flung regions of rural France, the use of special spoons wasn't widespread. But

they certainly were used, to some extent, throughout France and Switzerland, which is why the are found in their thousands throughout the

region. The testimony of two elderly Pontissalienne ladies quoted in Benoit Noel's book "L'Absinthe Un Mythe Toujours Vert" to the effect

that the use of absinthe spoons wasn't ever common in Pontarlier should be seen in this context, and taken with a grain of salt. Dozens,

probably hundreds, of posters and advertising cartons produced in Pontarlier and Couvet show absinthe being served with a perforated

spoon. My guess, is that these two old ladies, who would have been small children at the time of the ban, never entered a bar or café - they

would only have seen absinthe being drunk at home, where certainly perforated spoons were seldom used.

A popular alternative to using crystalized sugar (une absinthe au sucre) was to add either gum syrup (une absinthe gommée) or liqueur

d'anis (une absinthe anisée). Neither of these versions of course required a perforated spoon.

It was perfectly acceptable to drink an absinthe without sugar (une absinthe pure), but, based on all the historical evidence this certainly

wasn't the norm, and there is no publicity material extant from any manufacturer that suggests this was the primary method - it's always

referred to, if at all, as an alternative to the sugared version.

Occasionally absinthe was drunk diluted with other lower strength alcohol - white wine (une absinthe de minuit), or cognac (Toulouse

Lautrec's speciality, un tremblement de terre). But these were very unusual methods, which always aroused special comment, usually

disapproving.

Drinking neat absinthe (ie without water), certainly wasn't usual at any stage, and was never socially acceptable. Where it is referred to, it is

always in the context of alcoholism and degradation - in the same way, for instance, as we might refer to someone drinking a neat triple

gin today (the equivalent in alcohol content).

Today, modern absinthes are often marketed in conjunction with the so-called Bohemian absinthe ritual. This is not a traditional method,

but a modern innovation inspired by the success of flaming sambuca and such like. A shot of absinthe is poured into a glass, and a

teaspoonful of sugar is dipped into it. The alcohol soaked sugar is set alight and allowed to burn until it bubbles and caramelises. The

spoon of melted sugar is then plunged into the absinthe and stirred in, which usually sets the absinthe itself alight. Ice water is then

poured in, dousing the flames. This method, has become increasingly popular, especially since it was shown in the film “Moulin Rouge”,

but is a historical travesty, and would have horrified any Belle Epoque absintheur.

Absinthe is a strongly alcoholic aperitif made from alcohol and distilled herbs or herbal extracts, chief amongst them grand wormwood

(Artemisia absinthium) and green anise, but also almost always including 3 other herbs: petite wormwood (Artemisia pontica, aka

Roman wormwood), fennel, and hyssop. Some regionally authentic recipes also call for additional herbs like star anise (badiane), sweet

flag (aka calamus), melissa (aka lemonbalm or citronnelle), angelica (both root and seed), dittany (a type of oregano grown in Crete),

coriander, veronica (aka speedwell), marjoram or peppermint.

Grand and petite wormwood were historically cultivated near Pontarlier in the Doubs region of east France and in the adjoining Val de

Travers in Switzerland, the two traditional homes of absinthe, while the other herbs were shipped in: fennel from the Gard region of France

and even from Italy, the anise from the Tarn region or from Andalusia.

In modern Spanish absinthes star anise (badiane) is sometimes substituted wholly or partly for the green anise, but this tends to give a

very one dimensional liquorice-like taste. Badiane was used only very sparingly if at all in traditional Swiss or French manufacture. So

called Czech or German "absinths" sometimes omit the anise entirely, but these are not true absinthes and are best avoided. Home

"absinthe-making kits" widely advertised on the internet, and based on adding dried herbs or essences to vodka or Everclear, do not

produce even a rough approximation of the real drink - and the results, apart from being very unpleasant tasting, may be actively harmful.

High quality absinthes are always distilled rather than produced from herbal essences, and have a deliciously complex herbal and floral

character, with an underlying bitterness caused by the wormwood. The classic green absinthe verte is produced by a 3-step process: first

maceration of the herbal mixture in a base alcohol, then distillation of the resultant liquid and finally chlorophyllic coloration by gentle

heating of a further herbal infusion.

The absinthe distillation process was summarised by J. de Brevans in his 1908 La Fabrication des Liqueurs as follows:

Absinthe is made in accordance with a great number of recipes which are all based upon the following plants: grand wormwood, petite

wormwood, anise, fennel, and hyssop. In general these different plants are mixed together for distillation; but a few manufacturers prefer to

treat wormwood, anise and fennel separately, to later mix the scented spirits in the desired proportions.

The raw ingredients are placed into a steam-heated still, ...with the desired quantity of alcohol and half the volume of water needed for

distillation; the plants are allowed to macerate 12 to 24 hours or even longer; the rest of the water is added and distillation is started. ...This

operation is stopped as soon as the first spurt of distillate marks 60% (alcohol): rectification is thereby avoided.

The first part of the tails is collected separately and used to make absinthes ordinaire; only the heart is used to prepare fine absinthes. The

milky liquid which distills at the end is added to subsequent macerations.

Absinthe scented-spirit is colorless. To color it, a mixture of petite wormwood and hyssop is macerated; a colorator, a special apparatus

heated by steam or hot water circulation, is useful for this purpose; the process takes 12 hours.

Absinthe is put into barrels for aging, then reduced to desired proof before delivering for consumption.

Each herb adds its own subtle character to the blend - grand wormwood has both woody and bitter notes; petite wormwood is aromatic but

less bitter (and also useful for coloration); green anise gives its characteristic scent and rich smooth mouth-feel (which fennel also

enhances); the dried hyssop flowers contributes to the classic absinthe feuille morte (dead leaf) colour.

Well made absinthes are generally pale green, but louche, or turn milky, when water is added. This is caused by the essential oils

precipitating out of the solution, as the alcohol is diluted. Absinthes with a high percentage of star anise (or badiane as it is known in

France), such as those made in Spain, tend to have a very dramatic and opaque louche, while the louche in more traditionally made

absinthes develops slowly, and is more subtly translucent. Traditionally made absinthes are never a bright emerald green - those that are,

have artificial colouring added.

Clear absinthes - often called La Bleue or La Blanche, and historically popular in Switzerland - are made without the final colouring step,

and may also differ slightly in herbal composition (sometimes for instance containing génépi, which is not otherwise usually found in

absinthe). A red absinthe (originally probably coloured with paprika) has been made under the name Serpis for several decades in Spain,

but this is an isolated oddity.

The traditional strength is 55% - 72% alcohol, or 110º - 144º proof. Historically the best absinthes, including those from Pernod Fils, were

made from a base of grape alcohol, although cheaper grain or beet alcohols were also widely used.

Almost from its inception, absinthe has been known as “La Fée Verte” or “The Green Fairy”, a tribute to its reputedly seductive and

intoxicating powers.

How is absinthe drunk?

All true absinthes are bitter to some degree (due to the presence of absinthin, extracted from the wormwood) and are therefore usually

served with the addition of sugar. This not only counters the bitterness, but in well made absinthes seems also to subtly improve the

herbal flavour-profile of the drink.

The classic French absinthe ritual involves placing a sugar cube on a flat perforated spoon, which rests on the rim of the glass containing

a measure or “dose” of absinthe. Iced water is then very slowly dripped on to the sugar cube, which gradually dissolves and drips, along

with the water, into the absinthe, causing the green liquor to louche (“loosh”) into an opaque opalescent white as the essential oils

precipitate out of the alcoholic solution. Usually three to four parts water are added to one part of 68% absinthe. Historically, true

absintheurs used to take great care in adding the water, letting it fall drop by single drop onto the sugar cube, and then watching each

individual drip cut a milky swathe through the peridot-green absinthe below. Seeing the drink gradually change colour was part of its

ritualistic attraction.

One of the most evocative of all descriptions of the absinthe ritual is in Marcel Pagnol's The Time of Secrets:

"The poet's eyes suddenly gleamed.

Then, in deep silence, began a kind of ceremony.

He set the glass - a very big one - before him, after inspecting its cleanliness. Then he took the bottle, uncorked it, sniffed it, and poured out

an amber coloured liquid with green glints to it. He seemed to measure the dose with suspicious attention for, after a careful check and

some reflection, he added a few drops.

He next took up from the tray a kind of small silver shovel, long and narrow, in which patterned perforations had been cut.

He placed this contrivance on the rim of the glass like a bridge, and loaded it with two lumps of sugar.

Then he turned towards his wife: she was already holding the handle of a 'guggler', that is to say a porous earthenware pitcher in the shape

of a cock, and he said:

'Your turn, my Infanta!'

Placing one hand on her hip with a graceful curve of her arm, the Infanta lifted the pitcher rather high, then, with infallible skill, she let a very

thin jet of cool water - that came out of the fowls beak - fall on to the lumps of sugar which slowly began to disintegrate.

The poet, his chin almost touching the table between his two hands placed flat on it, was watching this operation very closely. The pouring

Infanta was as motionless as a fountain, and Isabelle did not breathe.

In the liquid, whose level was slowly rising, I could see a milky mist forming in swirls which eventually joined up, while a pungent smell of

aniseed deliciously refreshed my nostrils.

Twice over, by raising his hand, the master of ceremonies interrupted the fall of the liquid, which he doubtless considered too brutal or too

abundant: after examining the beverage with an uneasy manner that gave way to reassurance he signalled, by a mere look, for the

operation to be resumed.

Suddenly he quivered and, with an imperative gesture, definitely stopped the flow of water, as if a single drop more might have instantly

degraded the sacred potion."

Antique perforated spoons for use with absinthe are prized collectors items. There are hundreds of variants, some issued to

commemorate historic events like the opening of the Eiffel Tower in 1889, some representing intertwined absinthe leaves, others with

engraved advertising for one of the famous brands of the day. Almost all have been exhaustively catalogued by Marie Claude Delahaye, the

leading French authority on absinthe and absinthiana, and the author of numerous books on the subject.

A more unusual and labour-saving alternative to the perforated spoon was the absinthe brouilleur, a mixer that sat on top of the glass and

held both water and sugar, allowing the sugared water to automatically drip slowly into the glass. Also avidly collected are glasses,

carafes, ceramic pitchers and water fountains made specifically for use with the absinthe ritual.

There is some debate amongst absinthe historians as to when exactly the traditional absinthe ritual originated. Certainly, there is no

evidence that it was ever normal to drink absinthe neat, without water. Absinthe was drunk with the addition of both water and sugar from at

least the 1850's, and probably earlier. Absinthe was by no means unique in this respect - 19th century drinkers had a far sweeter tooth

when it came to alcohol than we have today, and other drinks and cordials were also regularly sweetened with sugar. They were usually

served with a long cordial spoon or a kind of swizzle stick, to help dissolve the sugar.

The use of a perforated spoon specifically for absinthe was a later development, which appears to have originated in the 1870's and only

became widespread in the 1880's and 1890's. From the 1890's onwards, it seems, on the evidence of existing engravings and cartoons,

that almost all absinthes in bars and cafés were served with a perforated spoon. However most satirical journals and such like reflected

specifically the Parisian scene, and it's possible that in far flung regions of rural France, the use of special spoons wasn't widespread. But

they certainly were used, to some extent, throughout France and Switzerland, which is why the are found in their thousands throughout the

region. The testimony of two elderly Pontissalienne ladies quoted in Benoit Noel's book "L'Absinthe Un Mythe Toujours Vert" to the effect

that the use of absinthe spoons wasn't ever common in Pontarlier should be seen in this context, and taken with a grain of salt. Dozens,

probably hundreds, of posters and advertising cartons produced in Pontarlier and Couvet show absinthe being served with a perforated

spoon. My guess, is that these two old ladies, who would have been small children at the time of the ban, never entered a bar or café - they

would only have seen absinthe being drunk at home, where certainly perforated spoons were seldom used.

A popular alternative to using crystalized sugar (une absinthe au sucre) was to add either gum syrup (une absinthe gommée) or liqueur

d'anis (une absinthe anisée). Neither of these versions of course required a perforated spoon.

It was perfectly acceptable to drink an absinthe without sugar (une absinthe pure), but, based on all the historical evidence this certainly

wasn't the norm, and there is no publicity material extant from any manufacturer that suggests this was the primary method - it's always

referred to, if at all, as an alternative to the sugared version.

Occasionally absinthe was drunk diluted with other lower strength alcohol - white wine (une absinthe de minuit), or cognac (Toulouse

Lautrec's speciality, un tremblement de terre). But these were very unusual methods, which always aroused special comment, usually

disapproving.

Drinking neat absinthe (ie without water), certainly wasn't usual at any stage, and was never socially acceptable. Where it is referred to, it is

always in the context of alcoholism and degradation - in the same way, for instance, as we might refer to someone drinking a neat triple

gin today (the equivalent in alcohol content).

Today, modern absinthes are often marketed in conjunction with the so-called Bohemian absinthe ritual. This is not a traditional method,

but a modern innovation inspired by the success of flaming sambuca and such like. A shot of absinthe is poured into a glass, and a

teaspoonful of sugar is dipped into it. The alcohol soaked sugar is set alight and allowed to burn until it bubbles and caramelises. The

spoon of melted sugar is then plunged into the absinthe and stirred in, which usually sets the absinthe itself alight. Ice water is then

poured in, dousing the flames. This method, has become increasingly popular, especially since it was shown in the film “Moulin Rouge”,

but is a historical travesty, and would have horrified any Belle Epoque absintheur.

| This website and all its contents Copyright 2002- 2009 Oxygenee Ltd. No pictures or text may be reproduced or used in any form without written permission of the site owner. |